The true nature of the crab: the delicious food arthropod you all know and love?

By Alyssa Leong

When eating crab, have you ever wondered whether you are actually eating the ancestor of an insect? Recently, I attended a talk by biologists regarding the crabs of Hong Kong.

Early on, the presenter introduced a slide with photos of various creatures and asked the audience to determine whether they were crustaceans—a broad group of invertebrate animals characterised by a hard exoskeleton and jointed pairs of appendages, among other key features. There were pictures of a sea turtle (definitely not a crustacean) and a hermit crab (a crustacean), which were quickly identified.

However, when it came to the harder questions, the audience was equally successful. When shown a picture of a horseshoe crab, the audience immediately identified that it was not a crustacean.

“Then what is it?” asked the biologist. To everyone's surprise, a 10-year-old child raised their hand to explain that it was in the subphylum Chelicerata, which also includes sea spiders and arachnids. Even the biologist was impressed!

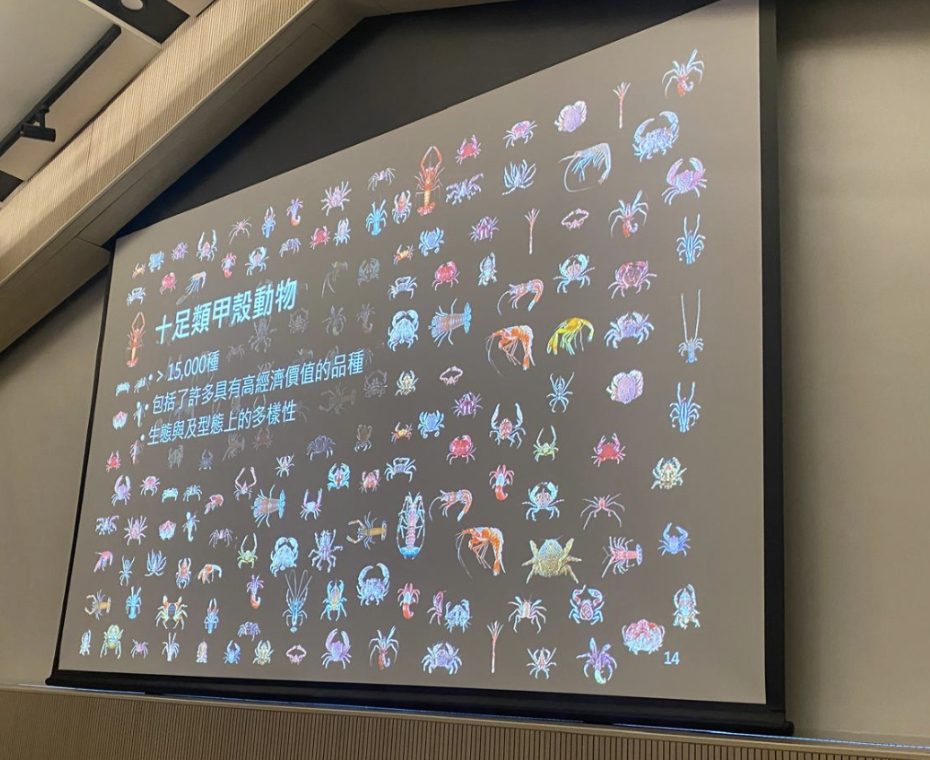

Afterwards, the biologist showed more pictures of creatures and asked us to decide whether or not they were "true crabs," a specific type of crustacean. True crabs are categorised in the infraorder Brachyura. They have five pairs of appendages and short antennae. Thus, animals such as the Alaskan king crab are not actually crabs; they have four pairs of walking legs, with the fifth pair reduced to a very small size. This points to their evolutionary relationship with hermit crabs, which have a specially developed, small fifth pair of legs for holding onto their shells. I had never heard of any of this and was amazed to see how much the audience knew.

At one point, the speaker described the evolution of crabs. According to molecular systematics research, insects evolved from crustaceans. However, since it is controversial to claim that insects are crustaceans and merge the categories, the term Pancrustacea is used to encompass both.

The definitions of animals were much more complex than I had realised. If we take DNA relationships to be the real defining factor, it seems my head was full of misconceptions regarding the nature of crabs. This created many mysteries: when I ate king crabs, was I unknowingly eating animals that are not, in fact, true crabs? Isn’t calling mutated hermit crabs “king crabs” false marketing? Shouldn’t we know that we’re eating a completely different kind of creature?

Additionally, the distinction between insects and crabs seems obvious. But now that I know they are so closely related, why do we consider crabs appealing and edible, yet view insects as repulsive and worthy of extermination—especially when the genetic differences between them are arbitrary?

Ultimately, that is rarely relevant in daily life. Most people just perceive a creature with a flattened body and a large number of legs as a crab, regardless of what its DNA says. King crabs and true crabs share the same habitat and shape, and both are delicious. Nevertheless, they are not genetically the same. Furthermore, we know that insects—even if they evolved from crustaceans—do not taste like crab and have a tendency to be pests.

It seems that sometimes, animals are defined primarily by how people perceive them rather than by their genetic makeup. The only significant biological difference relevant to us is that some people are allergic to king crabs but not to true crabs, and vice versa. The more you know.